First in a series of three articles

By: Susan Moffat-Thomas, retired Executive Director Swiss Bear Downtown Development

By the turn of the twentieth century, the high level of business activity on New Bern’s Trent waterfront ceased to exist. Post WW II suburban development, malls and the reduced use of railroads and water as a means of transportation, left many of the downtown waterfront commercial buildings vacant as businesses relocated to areas outside the city limits. The blighted dilapidated buildings, on the waterfront and in the central business district, continued to deteriorate becoming health and safety issues, hastening the deterioration and decline.

The advent of the auto and trucking industry and the 1944 Federal Highway Act set the stage for the widespread creation and exodus to the suburbs throughout the 50’s and 60’s. In New Bern, as the suburbs flourished, disinvestment plagued the downtown core retail area; little or no traffic, gaping holes in the streetscape, and slip covered storefronts. The 1979 mall opening was the final crushing blow. Many businesses followed, and Belk and Penny’s move to the mall left downtown with abandoned buildings and absentee owners. Adding to the deterioration, the industry and business abandonment of rivers and rails for super highways led to the deterioration of New Bern’s Trent River waterfront, creating a blighted tract of vacant buildings which became a vermin infested area.

A survey by the New Bern Planning Commission in mid-1960 determined the blighted three block commercial area along the Trent River, with its proximity to the central business district, was eligible for urban renewal grant funds. This opportunity appeared to have the greatest potential for revitalizing the downtown area. The federal program of land redevelopment, relocation of businesses and demolition of structures to revitalize decaying inner cities, was the leading national policy at the time.

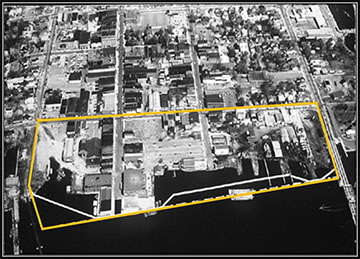

In July of 1967, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) approved a planning grant to the City of New Bern to “renew” the area. The 21-acre project area was bounded by East Front, Tryon Palace Drive (now South Front Street) Hancock Street and the Trent River and the city created a Redevelopment Commission in 1968 and appointed seven local businessmen including the Chamber’s executive director and an attorney, who were responsible for overseeing the objectives of the Urban Renewal Plan. This included, identifying land to be acquired for clearance; obtaining fee simple titles through negotiation or eminent domain; the removal/clearance of all structurally unsound structures; improving and widening existing street systems with adequate utilities, storm drainage and underground electrical distribution systems; preparing land for lease or resale for commercial and public uses as specified in the Urban Renewal Plan; raising the elevation of parts of the project area; construction of a bulkhead along the waterfront to reduce the threat of flooding, and constructing sidewalks along the waterfront for public use.

The estimated cost of the redevelopment project was $3.5 million. Locally, the city had to share in one-fourth of the cost (cash or improvements) estimated at $716,100. With the anticipated resale of the land, the estimated net project cost was $2.9 million. As the various stages of the project progressed, the Redevelopment Commission obtained temporary loans from the federal government. Federal capital grant progress payments and local grants-in-aid were made as needed over the life of the project.

All but three structures were demolished. The Harvey Mansion (ca. 1798) owned by the County, was rescued from the “wrecking ball” by local preservationists, who in an emergency effort, got it listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The other two buildings were owned by a water softening company and a finance company. All three buildings fronted the 200 block of Tryon Palace Drive (South Front Street). Demolition was completed by 1974.

Between the years of 1970–1973, the Redevelopment Commission was granted permission by the State of North Carolina, the Department of Army Corps of Engineers, NC Department of Conservation and Development Division of Commercial Sports Fisheries to hire an engineering and construction firm to dredge, design, and construct a bulkhead and fill in the irregular shoreline area, originally the site of warehouses, wharves, docks, marine railways and slips. Construction of the bulkhead, dredging and fill work, was completed by the end of 1974, representing an investment of $4.6 million including in-kind work by the city.

In 1974, Redevelopment Commission members made a concerted, yet unsuccessful, effort to market the entire area to one or more developers to no avail. A unified plan of development for the area had never been developed and the site was seen as dependent on the revitalization of the deteriorating downtown. To add to the challenge, HUD was pressuring the city and the Redevelopment Commission to bring the project to closure.

In 1976, Wachovia Bank & Trust Company purchased a lot at the corner of Middle Street and South Front Street and built a building for their new bank. Branch Bank purchased a parcel at the corner of South Front Street. In January 1977, the County purchased two parcels of property on the eastern side of Craven Street. The County’s plan to build a county office complex to include a new jail on the Trent waterfront generated widespread controversy. Articles in the Sun Journal, a political cartoon with prisoners fishing from their cell windows and letters to the editor, led to the failure of a bond issue for construction.

Another problem surfaced in 1977 when a local law firm, interested in building a new office complex on the urban renewal property, withdrew their offer when a problem arose in getting a clear title to the property that related to the land title of reclaimed underwater lands. Even though all dredge and fill permit regulations were complied with, and the State of North Carolina had delivered a Quit-Claim Deed to the Redevelopment Commission for the land reclaimed by dredging and filling, it became evident that land titles would be subject to the rights of the United States by reason of federal control over navigable waters, i.e., that section had to be removed from “federal navigable waters” jurisdiction so a clear title could be obtained by property owners. City Attorney, Al Ward, sought assistance from Congressman Walter B. Jones, Senator Jesse Helms and Senator Robert Morgan. Introduced as part of a bill, it did not pass. The issue was finally solved when it was tacked on to Public Law 96-520, and became a U. S. law in December of 1980.

In the meantime, the Redevelopment Commission closed the project out, conveying the unsold portions of the urban renewal land to the city in 1978. With the celebration of the U.S. Bicentennial, this vast vacant tract became known as Bicentennial Park and was used for public events and recreational fields, as the city and county began selling lots in a piecemeal fashion.

Developing a Unified Plan – To be continued in the March NBM issue.