by Edward Ellis, Special Correspondent

In early 1865, a newspaper letter writer complained that “there are no two time-pieces that agree, and everyone is ready to swear that his watch or clock is right.” The solution the correspondent to the New Bern Times suggested was the ringing of the bell at the Methodist Church on New Street, which he said had “the largest and best-sounding bell in the city.”

New Bern was under the control of the Union Army from 1862 to 1865. In this instance, the writer urged the provost marshal to have a bell rung at noon and 9 p.m. each day claiming it “would be heard by all throughout the town.”

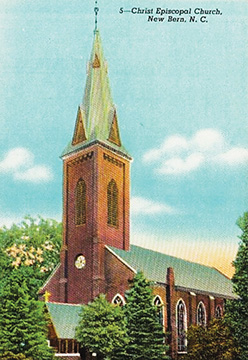

A few weeks later, the paper’s editor reiterated the suggestion. Not long after that, the twice daily bell ringing commenced under the supervision of the town’s postmaster, George W. Nason, Jr. But not from Centenary Methodist. The bell of Christ Episcopal began keeping time on February 24, 1865. And not without challenges. When the bell rang briskly at 9 p.m. that evening, a hubbub arose as many people reacted to what they took to be “an alarm of fire.”

The church bell-ringing of 1865 was the re-institution of a practice begun shortly after Northern force seized the city. On August 5, 1862, the then-provost marshal, Col. John Kurtz, published a notice in the Newbern Daily Progress that the bell of the church on Pollock Street would be rung twice daily “to establish correct time in this city.” A few days later, a minor calamity: “As the bell of the Episcopal Church was ringing at 12 [midday] … the bell became detached from its fastenings and fell through the bell deck. We understand that the bell was fractured in the operation.”

But even when church bells weren’t ringing, folks downtown heard the bells of the many ships and gunboats populating the waterfront. Ship’s bells marked the sailors’ shift changes and thereby provided a handy reference for the time of day.

Sometimes the bells rang for more somber purposes. On September 23, 1862, New Bern’s Union commander, Gen. John G. Foster, ordered bells rung and guns fired “in honor of the gallant Gen. [Jesse L.] Reno, who fell at the battle of South Mountain. A general feeling of sadness pervades this community, for both soldiers and citizens had learned to love and respect him,” a newspaper reported.